With Earth Day fast approaching, the Vernon Museum has taken the opportunity to research how local human activity has effected, and continues to effect, ecosystems and wildlife in the North Okanagan.

Until the end of April, the museum will share a series of articles that explore some of the results of this investigation.

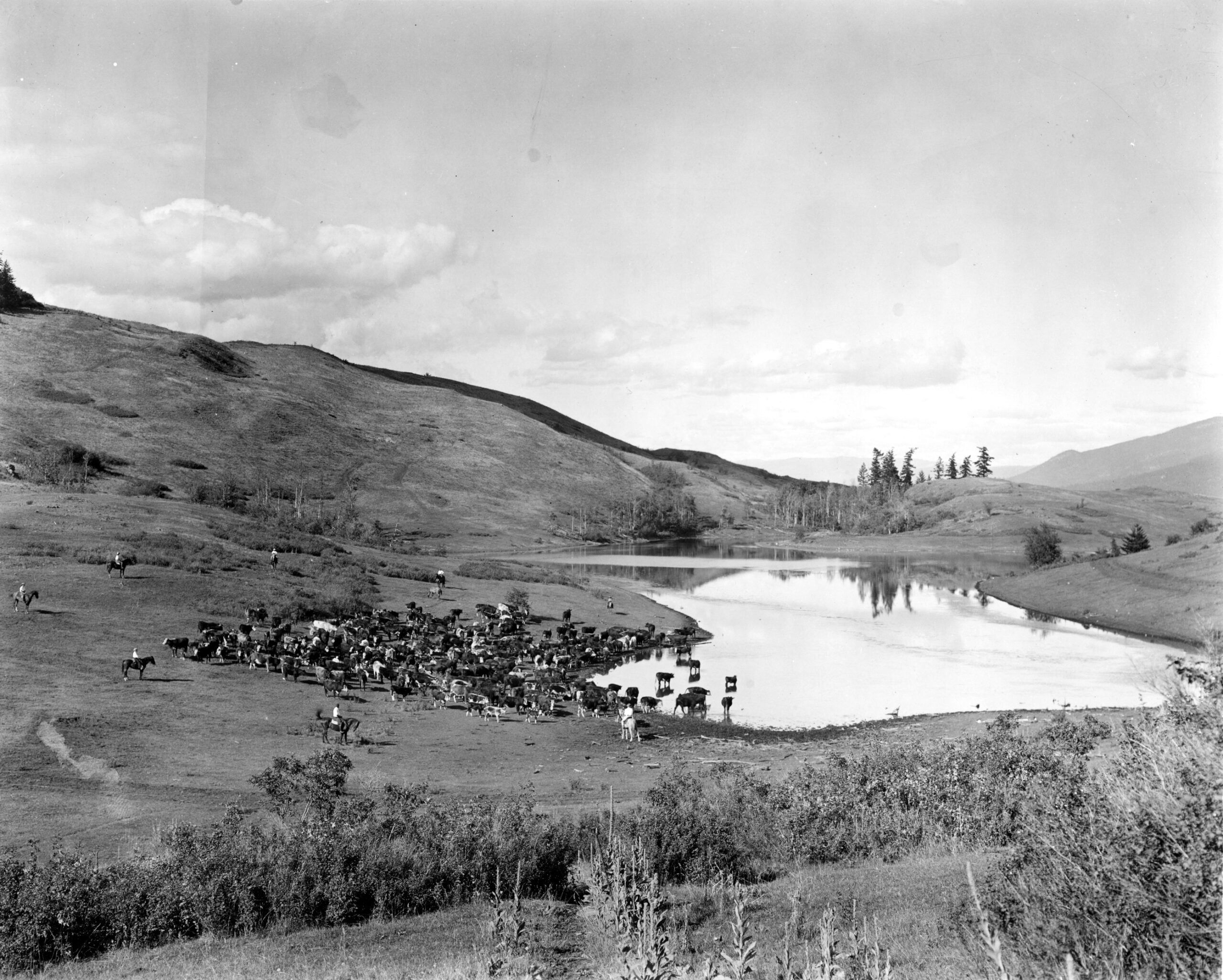

The importance of the introduction of cattle to the Valley cannot be overstated.

Early cattle drives passed through the Valley in the late 1850s, where the animals would feast on the Okanagan’s abundant bunchgrass, before continuing on their way to the gold fields of the Fraser Canyon.

By the end of the next decade, upwards of 22,000 head of cattle had crossed the border at the south end of the Okanagan Valley.

Early cattle drives, and, later, the establishment of ranches, allowed the Okanagan to become a hub of economic activity. Despite this benefit, the arrival of large droves of cattle inevitably shaped the natural landscape in lasting ways.

Later, pioneers like Thomas Wood, Thomas Greenhow, and Cornelius O’Keefe arrived to pre-empt land and start permanent ranches. Their small herds grew rapidly in number.

The Okanagan of 1850s and ‘60s would have been almost unrecognizable to us today. The Valley bottom was covered not with areas of human development, but with fields of tall grass that, as they swayed in the breeze, resembled a vast, moving sea.

These grasses were especially adapted to our warm, dry climate. In particular, bunchgrass, of which there are several different species in the Okanagan, has a deep root system as well as a specific morphology which allows it to survive long periods of drought.

This bunchgrass was also perfect animal fodder and after a decade or so of constant feeding, the bunchgrass population began to suffer. By the 1890s, much of the bunchgrass had been stripped from the Valley.

Since then, the science of range management has progressed greatly, and it’s not the ranches that prove the greatest threat to native bunchgrass, but human encroachment. Areas of bunchgrass can still be found (at Kalamalka Lake Park, for example) but what was once a sea of grass is now only a few sparse patches. Today, only 9% of native bunchgrass is left in the Okanagan.

There are many approaches that we can take to curb the destruction of native bunchgrass populations, including supporting ecological restoration and habitat renewal initiatives, remaining on trails and marked areas when hiking and biking, learning about the growth cycle of plants and making informed decisions when allowing animals to graze, and taking an active role in preventing the spread of invasive weeds.

If you are interested in learning more about this topic, an excellent read is “Bunchgrass and Beef: Bunchgrass Ecosystems and the Early Cattle Industry in the Thompson-Okanagan,” by local historian Ken Mather, available online at https://royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/exhibits/living-landscapes/thomp-ok/article-LL/contents-beef.html.

Gwyn Evans